Davide Oliviero, 30 June 2025

GnamC (Rome): YOKTUNUZ by Ahmet Güneştekin

GnamC – National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art of Rome: YOKTUNUZ by Ahmet Güneştekin. Curated by Sergio Risaliti and Paola Marino, with organizational direction by Angelo Bucarelli

Rome, June 30, 2025

Ahmet Güneştekin’s exhibition YOKTUNUZ at the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art is not just a show—it’s a silent detonation at the heart of the institution. A sculptural environment of memory and trauma, it creeps into the museum’s rhetoric like a splinter, infected and infecting.

It’s no surprise, then, that what caused the scandal wasn’t the content, the historical references, or the political tensions, but—almost farcically comic, like an Italian-style sham—the smell. Yes, the smell. Because in 2025, art becomes unsettling when it’s no longer scentless, when it drags visitors out of their climate-controlled aesthetic comfort zone and forces them to perceive, if only for a moment, the presence of a decaying reality. The black shoes that make up Reminiscence Bump, one of the most radical pieces in the exhibition, triggered collective complaints: museum staff wearing facemasks, annoyed tour guides, press releases by union of workers, and requests for inspections by the local health authority. Yet, this work does nothing else but bring into the GNAM the physical presence of what visual culture tries so hard to dismiss: the body without aesthetic appeal, matter without purification, absence stripped of beauty. Ahmet Güneştekin, a Turkish artist of Kurdish origin, has long worked with an aesthetics of loss that doesn’t comfort but accuses. His works don’t illustrate a message—they embody it.

It’s no surprise, then, that what caused the scandal wasn’t the content, the historical references, or the political tensions, but—almost farcically comic, like an Italian-style sham—the smell. Yes, the smell. Because in 2025, art becomes unsettling when it’s no longer scentless, when it drags visitors out of their climate-controlled aesthetic comfort zone and forces them to perceive, if only for a moment, the presence of a decaying reality. The black shoes that make up Reminiscence Bump, one of the most radical pieces in the exhibition, triggered collective complaints: museum staff wearing facemasks, annoyed tour guides, press releases by union of workers, and requests for inspections by the local health authority. Yet, this work does nothing else but bring into the GNAM the physical presence of what visual culture tries so hard to dismiss: the body without aesthetic appeal, matter without purification, absence stripped of beauty. Ahmet Güneştekin, a Turkish artist of Kurdish origin, has long worked with an aesthetics of loss that doesn’t comfort but accuses. His works don’t illustrate a message—they embody it.

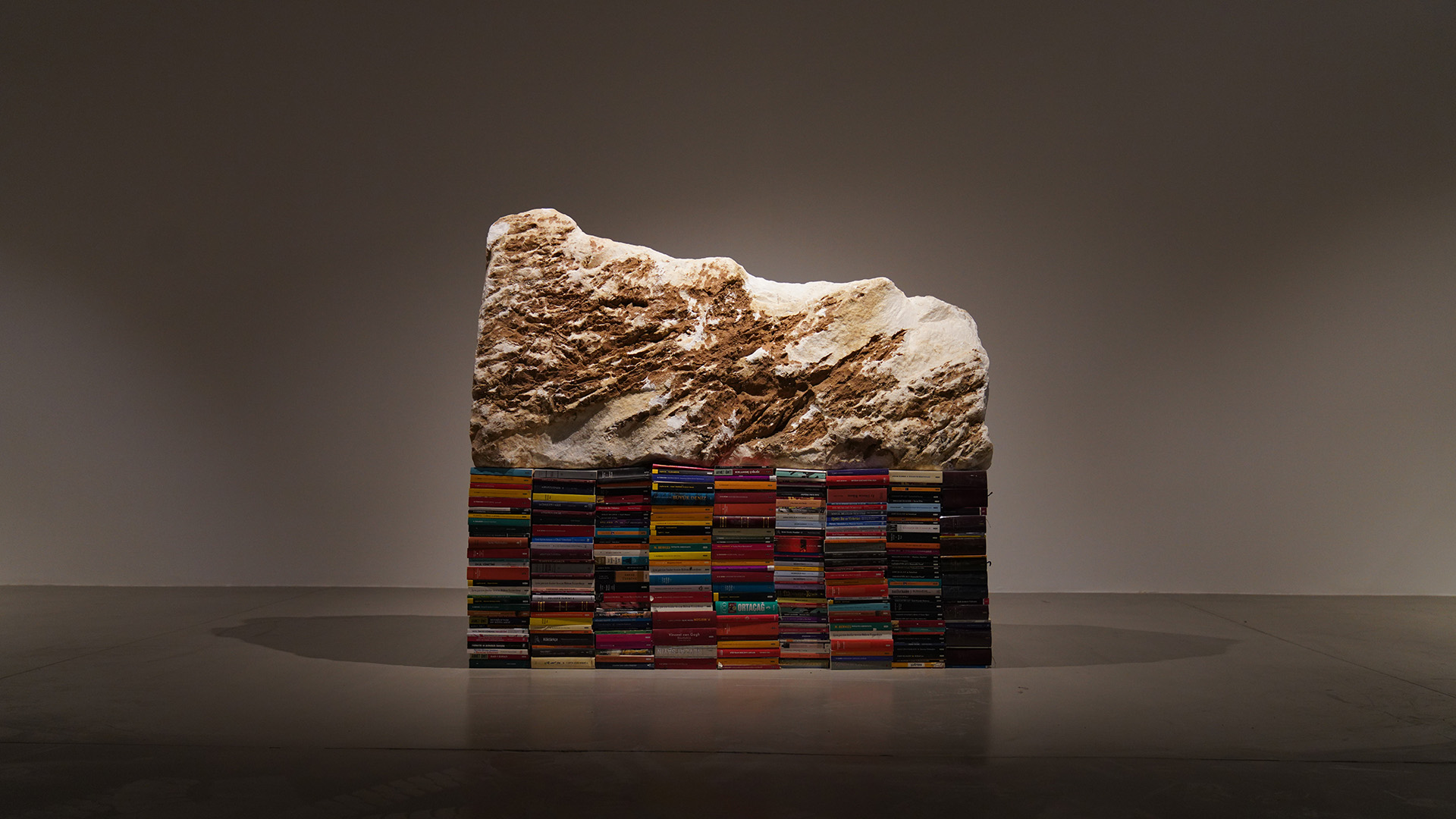

These works don’t settle for evocation; they rebel. And if art is also about dysfunction, as a long line from Artaud to Beuys has shown, then the stench —yes, the stench — is the symbolic excess that lays bare the gap between representation and reality. Deportation doesn’t smell like lavender, prisons don’t smell like incense, genocide has no trace of air freshener. In an age when even the aesthetics of catastrophe has been sweetened to make it marketable, Güneştekin brings back into the museum what the museum had sterilized: the political body of art. Let’s not be too quick to misread it: YOKTUNUZ is not an ‘odorous’ exhibition. It’s a dense one. It doesn’t begin and end with Reminiscence Bump, nor does it boil down to dissension. The exhibition unfolds through monumental works that examine form through trauma, colour through mourning, and material through history. Totemic sculptures, oxidized metal surfaces, and visual patterns that evoke a pan-Mediterranean rituality — de-territorialised yet stubbornly Eastern — map out a mental geography of resistance. Not armed resistance, but plastic resistance.

These works don’t settle for evocation; they rebel. And if art is also about dysfunction, as a long line from Artaud to Beuys has shown, then the stench —yes, the stench — is the symbolic excess that lays bare the gap between representation and reality. Deportation doesn’t smell like lavender, prisons don’t smell like incense, genocide has no trace of air freshener. In an age when even the aesthetics of catastrophe has been sweetened to make it marketable, Güneştekin brings back into the museum what the museum had sterilized: the political body of art. Let’s not be too quick to misread it: YOKTUNUZ is not an ‘odorous’ exhibition. It’s a dense one. It doesn’t begin and end with Reminiscence Bump, nor does it boil down to dissension. The exhibition unfolds through monumental works that examine form through trauma, colour through mourning, and material through history. Totemic sculptures, oxidized metal surfaces, and visual patterns that evoke a pan-Mediterranean rituality — de-territorialised yet stubbornly Eastern — map out a mental geography of resistance. Not armed resistance, but plastic resistance.

Not a discourse on freedom, but single combat with oblivion. At the very heart of the museum—a space consecrated to constructing post-unification national identity—Güneştekin plants a kind of iconoclasm that is subtle, but viral. His works don’t merely exist: they infest. They don’t seek dialogue with the permanent collection: they undermine it. Next to Canova’s neoclassical marble Hercules and Lichas, the installation YOKTUNUZ raises a counter-monument to absence. Where Canova exalts neoclassical heroism, Güneştekin lays bare the void left by the defeated of History. It’s a silent act of sabotage — a counter-narrative made of scorched matter and unprocessed weight. The exhibition moves like a secular ritual, where the sacred is no longer vertical but horizontal, etched into the skin of things, layered into the material itself. There is no solemnity here, only fever. No contemplation, only exposure. Each work is an act of symbolic insubordination: the oxidized iron, the exaggerated chromatic layering, the obsessive rhythm of forms don’t speak to the eye, but to the nerve.

Not a discourse on freedom, but single combat with oblivion. At the very heart of the museum—a space consecrated to constructing post-unification national identity—Güneştekin plants a kind of iconoclasm that is subtle, but viral. His works don’t merely exist: they infest. They don’t seek dialogue with the permanent collection: they undermine it. Next to Canova’s neoclassical marble Hercules and Lichas, the installation YOKTUNUZ raises a counter-monument to absence. Where Canova exalts neoclassical heroism, Güneştekin lays bare the void left by the defeated of History. It’s a silent act of sabotage — a counter-narrative made of scorched matter and unprocessed weight. The exhibition moves like a secular ritual, where the sacred is no longer vertical but horizontal, etched into the skin of things, layered into the material itself. There is no solemnity here, only fever. No contemplation, only exposure. Each work is an act of symbolic insubordination: the oxidized iron, the exaggerated chromatic layering, the obsessive rhythm of forms don’t speak to the eye, but to the nerve.

This exhibition doesn’t seek to please: it seeks to remain. It doesn’t ask for approval, but for attention. In an art world where political correctness and spiritual decorativism anesthetize everything, Güneştekin disrupts the canon with unavoidable brutality. The figures that emerge from his work are not characters but presences—neither figurative nor abstract, neither mythical nor historical. They are liminal projections, archetypes contaminated by centuries of violence and neglect. They don’t tell a story—they carry its remains. They are not icons, but symptoms. Their bodies aren’t made to be seen, but to be felt. Exile is not a theme here: it’s an emotional landscape the viewer is forced to walk through without a map. Each work is a wound that refuses to heal, a palimpsest of omissions and survivals. This is where Güneştekin’s intervention reaches its most powerful point: YOKTUNUZ isn’t an exhibition about memory—it’s a device that activates repression. It doesn’t tell: it evokes. It doesn’t represent: it presents.

This exhibition doesn’t seek to please: it seeks to remain. It doesn’t ask for approval, but for attention. In an art world where political correctness and spiritual decorativism anesthetize everything, Güneştekin disrupts the canon with unavoidable brutality. The figures that emerge from his work are not characters but presences—neither figurative nor abstract, neither mythical nor historical. They are liminal projections, archetypes contaminated by centuries of violence and neglect. They don’t tell a story—they carry its remains. They are not icons, but symptoms. Their bodies aren’t made to be seen, but to be felt. Exile is not a theme here: it’s an emotional landscape the viewer is forced to walk through without a map. Each work is a wound that refuses to heal, a palimpsest of omissions and survivals. This is where Güneştekin’s intervention reaches its most powerful point: YOKTUNUZ isn’t an exhibition about memory—it’s a device that activates repression. It doesn’t tell: it evokes. It doesn’t represent: it presents.

Absence isn’t thematized: it becomes body, obstacle, substance. Art returns as an intrusive presence in the museum, which turns from a space of celebration into a stage for confrontation. Who has the right to be displayed? What pain is allowed? Who can afford not to be pleasing? Thus, the outrage over the smell of the shoes is merely a symptom of a deeper discomfort—the discomfort of a cultural system that no longer tolerates excess, that hides behind decorum, and mistakes what’s pleasant for what’s right. With razor-sharp irony, Güneştekin understands this better than anyone else: “Death doesn’t smell nice.” That’s not a punch-line. It’s a critical axiom. A reversal of museum culture’s desire to mourn without getting dirty, to remember without touching, to commemorate without compromising. And here lies the paradox: the real scandal isn’t the smell. The real scandal is that there’s still an artist capable of disturbing.

Absence isn’t thematized: it becomes body, obstacle, substance. Art returns as an intrusive presence in the museum, which turns from a space of celebration into a stage for confrontation. Who has the right to be displayed? What pain is allowed? Who can afford not to be pleasing? Thus, the outrage over the smell of the shoes is merely a symptom of a deeper discomfort—the discomfort of a cultural system that no longer tolerates excess, that hides behind decorum, and mistakes what’s pleasant for what’s right. With razor-sharp irony, Güneştekin understands this better than anyone else: “Death doesn’t smell nice.” That’s not a punch-line. It’s a critical axiom. A reversal of museum culture’s desire to mourn without getting dirty, to remember without touching, to commemorate without compromising. And here lies the paradox: the real scandal isn’t the smell. The real scandal is that there’s still an artist capable of disturbing.

That YOKTUNUZ achieves this without special effects, without immersive technology, without slogans, but solely through material, form, and insistence, is its greatest strength. In an exhibition landscape that increasingly slips into simulation, Güneştekin restores to the museum its original function: a space of rupture, friction, and vertigo. For those in search of art that comforts, the next room is always available. For those who still need art that burns, YOKTUNUZ waits in a side room, reminding us that when absence takes form, it doesn’t ask for permission. And it doesn’t need to smell nice.

That YOKTUNUZ achieves this without special effects, without immersive technology, without slogans, but solely through material, form, and insistence, is its greatest strength. In an exhibition landscape that increasingly slips into simulation, Güneştekin restores to the museum its original function: a space of rupture, friction, and vertigo. For those in search of art that comforts, the next room is always available. For those who still need art that burns, YOKTUNUZ waits in a side room, reminding us that when absence takes form, it doesn’t ask for permission. And it doesn’t need to smell nice.